Bogus Bride

The University of Arizona Press passed off I Married Wyatt Earp as a historical document. It's not.

Andrew Richard Albanese

Salon.com - Tuesday, Feb 8, 2000

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

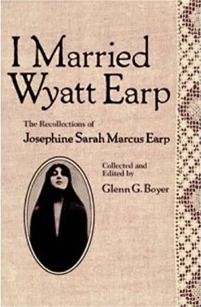

In 1976, the University of Arizona Press first published I Married Wyatt Earp, a memoir by Josephine Earp, the third wife of America’s most storied frontier legend, edited by an amateur historian named Glenn Boyer. Over the years the book has sold nearly 35,000 copies, a surprising commercial success driven primarily by its never-before-seen first-person accounts of Wyatt Earp in Tombstone, Ariz., and the events surrounding the infamous gunfight at the OK Corral. There is just one problem. According to historians of the West, the book is a fraud.

In 1976, the University of Arizona Press first published I Married Wyatt Earp, a memoir by Josephine Earp, the third wife of America’s most storied frontier legend, edited by an amateur historian named Glenn Boyer. Over the years the book has sold nearly 35,000 copies, a surprising commercial success driven primarily by its never-before-seen first-person accounts of Wyatt Earp in Tombstone, Ariz., and the events surrounding the infamous gunfight at the OK Corral. There is just one problem. According to historians of the West, the book is a fraud.

“I’m really shocked by the University of Arizona Press,” says Allen Barra, a journalist and the author of the recent book Inventing Wyatt Earp: His Life and Many Legends (Caroll & Graf, 1998). “Fraud has been committed here, but that is no longer the story. The story is that the University of Arizona Press is perpetuating this fraud, and they’ve known about it from the beginning.”

According to Barra, the controversy began in the early 1990s, when historians began to doubt the existence of a collection of Josephine’s personal memoirs, known as the Clum manuscript, that Glenn Boyer claims he used to create the vital Tombstone section of I Married Wyatt Earp. But the rumbling escalated into a full-fledged scandal in October 1999. That’s when newly appointed University of Arizona Press director Christine Szuter wrote to Barra, who had been prodding the press for years to investigate Boyer’s sources, and acknowledged that there was a problem with the book.

To remedy the problem, Szuter wrote, the press intended to “redesign the cover and rewrite the cover copy, change the authorship from Josephine Earp to Glenn Boyer, and add a publisher’s note regarding sources used in the book.” A puzzling response, says Barra, who was furious that a scholarly press, or any press for that matter, could be so cavalier with such fundamental issues as authorship and the authenticity of sources. Change it to I Married Wyatt Earp by Glenn Boyer? “Is that not tantamount to an admission of fraud?” asks Barra. “How can you say for 23 years that a book is a memoir, let it be used as a primary source for historians, and then say all of a sudden that it is fictional and that everyone should have known it was fictional all along? Can anyone offer any parallel for this?”

Even more troubling than Szuter’s proposed solution is the fact that in the past month the University of Arizona has instituted a media blackout on the subject of Boyer and has referred all questions about I Married Wyatt Earp to university lawyers. University of Arizona attorney Mike Proctor confirmed that “a full review” of the “publication issues” surrounding the book was under way, but that no one at the press or the university would speak on the matter. “That is solely because of inaccurate media coverage, no other reason,” noted an obviously peeved Proctor. “I have been very open up to the point where we got burned and now we just can’t go there.”

Proctor would not say on the record who in the media had “burned” the university or what “publication issues” his office is delving into. But he did angrily single out one publication for misreporting information: the Daily Wildcat, the student newspaper of the University of Arizona. Contrary to what that paper reported, says Proctor, his office would not be reviewing Boyer’s questionable sources. “I am not qualified to look at sources, I am a lawyer.” So what is Proctor looking at if not claims that the author fudged his sources? “I am just looking at our entire file on the book, start to finish, trying to identify objectively publication issues, and then work toward the best resolution of those issues.” Would charges of academic fraud and creating fictional source material be considered publication issues? Proctor would not say. “Sorry, but you’re all getting the same thing. No comment.”

“A public university refusing to talk to the press? Richard Nixon would be proud,” says Casey Tefertiller a Bay Area journalist and the author of Wyatt Earp: The Man Behind the Legend (John Wiley and Sons, 1997). Like Barra, Tefertiller has been a vocal critic of the university and Boyer. “If you feel you have been misrepresented in the press, you don’t institute a blackout, you insist on a correction. For a journalist, all a blackout does is hint that there is a story there after all.”

According to Los Angeles New Times reporter Tony Ortega, who was a reporter in Phoenix in 1998, there definitely is a story. Ortega is the man credited by many with blowing the cover off I Married Wyatt Earp in a 1998 series of articles in the Phoenix New Times by doing what many critics of Boyer had not the time or the stomach to do. Tipped off by Barra to the increasingly bizarre controversy brewing in his backyard, Ortega visited Boyer in the summer of 1998 at his sprawling Arizona ranch. There he learned that Boyer could not, indeed, produce the source material he claimed to possess, specifically, the disputed Clum manuscript.

Ortega then contacted the University of Arizona Press and filed a public records request to view its files and correspondence on the matter. He was taken aback by the press reaction to his request. “They treated me as this hostile enemy,” says Ortega. “I was just doing my job, asking simple questions.” After much stalling, Ortega was eventually permitted to look at the files. It was then, he recalls, that the bunker mentality of the press finally made sense.

“That’s really where the smoking gun was,” says Ortega. “It was bad enough that Boyer was admitting to me that he was including all these things that Josephine Earp hadn’t actually done herself, but here were the documents to show that the University of Arizona Press was asking Boyer to embellish things. It was clear that the University of Arizona Press not only knew his sources were suspect, but they encouraged him to embellish.”

Critics charge that the bizarre, often conflicting defenses offered by Boyer should have sent a up a red flag to University Press officials that something was amiss from the very beginning. According to respected Western historian Gary Roberts, a professor at Abraham Baldwin College in Georgia, Boyer has often claimed that he can produce every shred of the documentation that he claims to have, but somehow he never does. Boyer has also at times advanced the strange notion that his work engages in “terminological inexactitude,” a tactic involving a hidden gauntlet of purposely laid-out misinformation within his books intended to trap sloppy historians. And finally, Boyer himself has admitted that he is not a historian at all but a “novelist, and a damn good one,” engaged in the art of “creative nonfiction.”

And then there are Boyer’s wild personal attacks against those who question his work. “Boyer has accused almost everyone involved in this saga of homosexuality, pedophilia, rape or drunkenness,” says Tefertiller, who has been on the receiving end of more than a few Boyer attacks. “He accused Allen Barra of being fat.”

Now there’s an author a university press can hang its 10-gallon hat on. But is the University of Arizona Press really staking its reputation on a work of creative nonfiction and on an author who replies to questions of scholarship with crude innuendo?

*****************************

Link to original article: http://www.salon.com/2000/02/08/earp/

Managed by Tombstone Historians